Project Maleth is Malta’s first opportunity to be directly part of the ever-growing space industry. It is the first Maltese biomedical experiment, headed by Prof. Joseph Borg and his team, to be launched in space with the aim of shedding some light on how the bacterial biome of infected foot ulcers of diabetic patients, will react to the harsher environment of outer space. Glenn Sciortino from Arkafort talks about the technical side of the experiment and the recent visit to the Space Applications Services in Belgium to place the samples in the Biocube before launching to space.

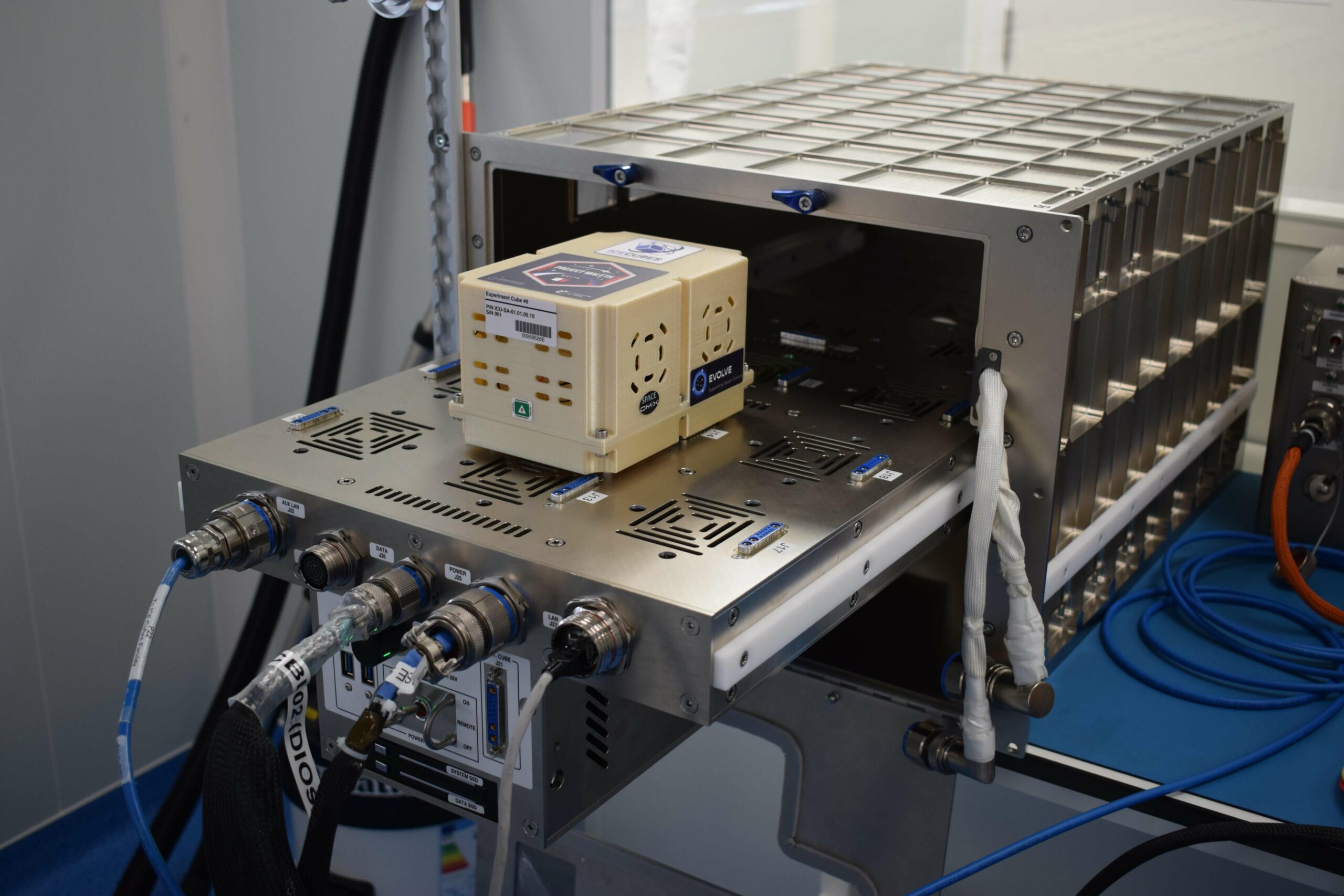

The experiment is essentially being conducted on six separate foot ulcer skin samples, taken from six different diabetic patients. Given that the ISS is a contained environment, the astronaut’s health and well being is always top priority. So how does one send biomaterial to the ISS, carry out the necessary experiments, while also ensuring the safety of the crew on board? That is where the ICE Cube comes in. The ICE Cube is a product being developed by Space Applications Services, an independent Belgian company founded in 1987, with a subsidiary in Houston, USA. The idea behind the ICE Cube service is to make such experiments not only possible, but also practical and feasible. Prof. Borg and myself had the opportunity to visit their headquarters in Brussels last week to witness the final stages of the cube, ahead of its launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, in two weeks time as part of the SpaceX CRS-23 resupply mission.

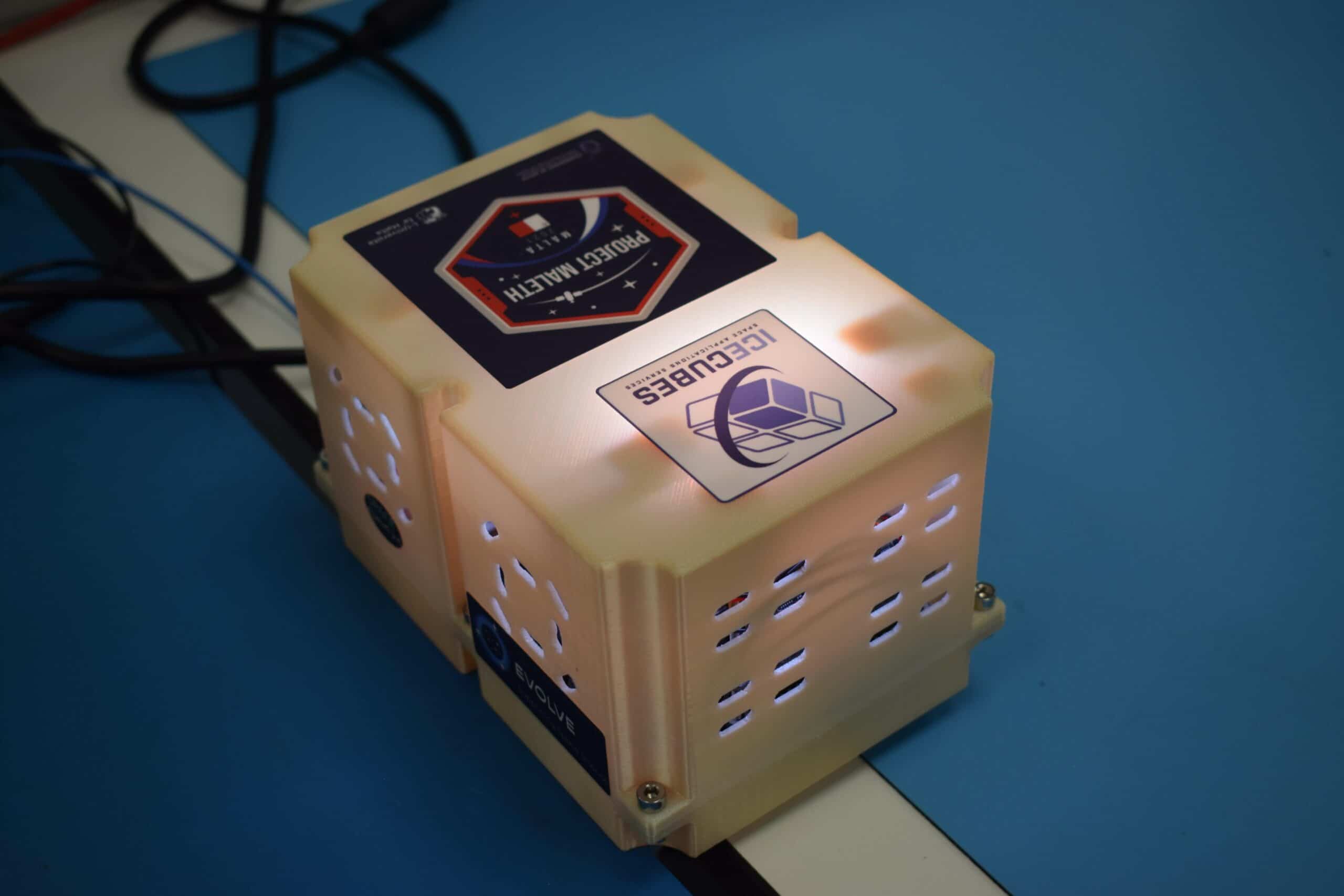

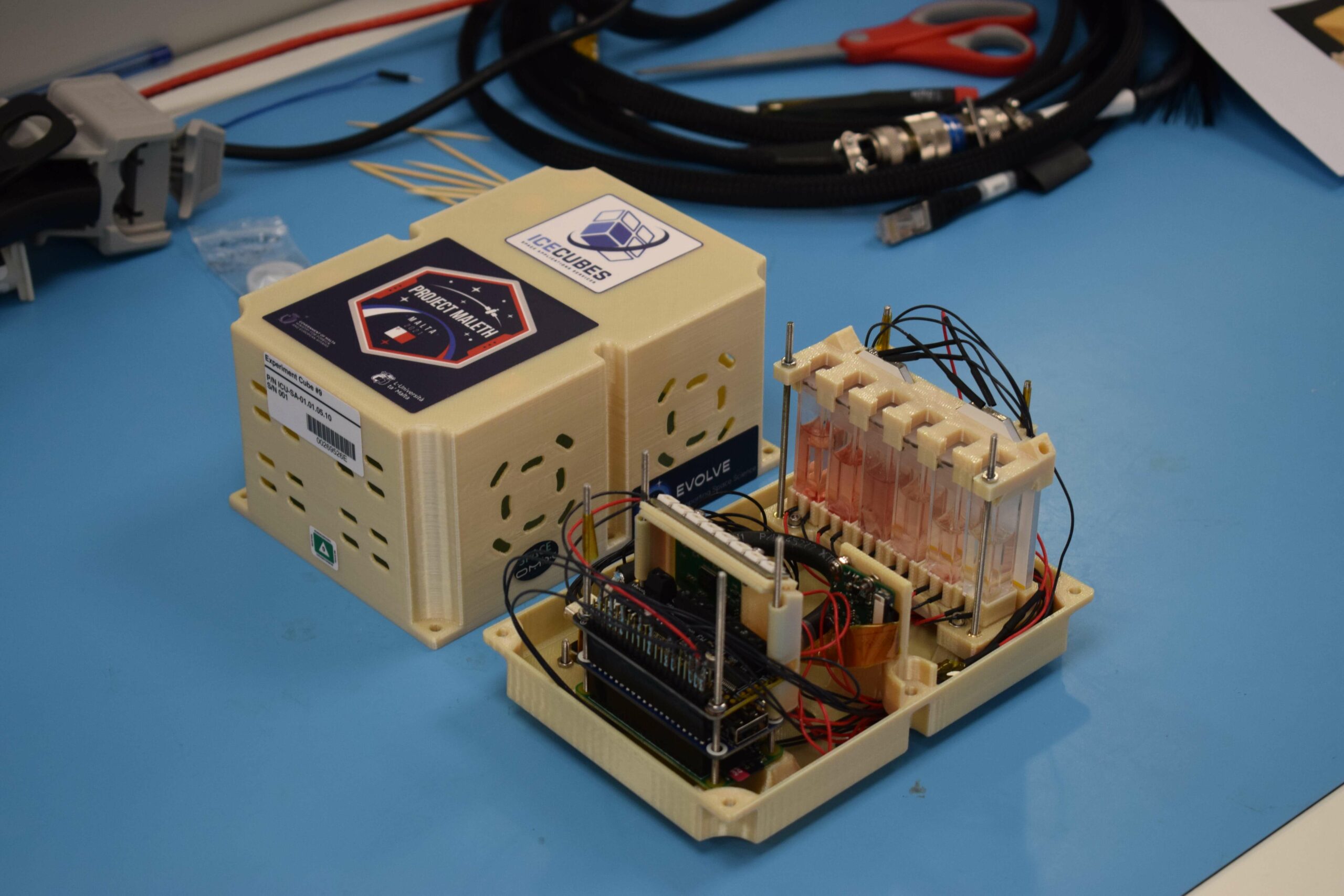

The cube itself consists of a 3D printed outer shell with a form factor that varies according to the experiments being carried out. Project Maleth’s experiment required the use of small plastic cuvettes to contain the skin samples within a PBS (Phosphate-Buffered Saline) solution, and therefore the internal part of the cube had to be designed in such a way as to accommodate six of these cuvettes. Along with the cuvettes, the cube has to cater for an array of electronics, which interestingly enough, are mostly made up of commercially available off-the-shelf components. This drastically reduces the cost of the cube.

The main computer consists of a Raspberry Pi Zero, two small cameras and a number of expansion boards or ‘hats’ which expose the Pi’s GPIO pins and enable network connectivity. The computer enables the researchers to interact with the cube once it is latched to the ICE Cubes framework within the Colombus module onboard the ISS and monitor the samples for the duration of the mission which will be around 50 to 60 days. Along with the two cameras that are able to snap real-time pictures of the cuvettes and also stream live videos, are three sets of LEDs which allow for a range of lighting conditions within the cube. The first set behind the cuvettes serves as a backlight. The second set underneath, allows for the individual illumination of the cuvettes and the third one angled at a 45 degree angle to the ceiling of the cube, provides soft RGB lighting.

The act of connecting to the cube once it’s safely on board the ISS, is where it gets interesting. Internet connectivity on the ISS is facilitated through the same network of tracking and data relay satellites (TDRS) that NASA engineers use for telemetry data and to communicate with the crew on board. The internet connection is relatively slow when compared to what we are used to here on earth, and has very high latency due to the vast distances that the signal has to cover in order to reach its destination. The ISS – at an altitude of 400 kilometres above the earth (also known as low earth orbit) – has to first beam its signal to one of these geosynchronous relay satellites, which can sometimes reach altitudes 90 times higher than that of the ISS. The satellite then beams the signal to a ground station where it processes the request and replies via the same request path.

The cube itself consists of a 3D printed outer shell with a form factor that varies according to the experiments being carried out. Project Maleth’s experiment required the use of small plastic cuvettes to contain the skin samples within a PBS (Phosphate-Buffered Saline) solution, and therefore the internal part of the cube had to be designed in such a way as to accommodate six of these cuvettes. Along with the cuvettes, the cube has to cater for an array of electronics, which interestingly enough, are mostly made up of commercially available off-the-shelf components. This drastically reduces the cost of the cube.

The main computer consists of a Raspberry Pi Zero, two small cameras and a number of expansion boards or ‘hats’ which expose the Pi’s GPIO pins and enable network connectivity. The computer enables the researchers to interact with the cube once it is latched to the ICE Cubes framework within the Colombus module onboard the ISS and monitor the samples for the duration of the mission which will be around 50 to 60 days. Along with the two cameras that are able to snap real-time pictures of the cuvettes and also stream live videos, are three sets of LEDs which allow for a range of lighting conditions within the cube. The first set behind the cuvettes serves as a backlight. The second set underneath, allows for the individual illumination of the cuvettes and the third one angled at a 45 degree angle to the ceiling of the cube, provides soft RGB lighting.

The act of connecting to the cube once it’s safely on board the ISS, is where it gets interesting. Internet connectivity on the ISS is facilitated through the same network of tracking and data relay satellites (TDRS) that NASA engineers use for telemetry data and to communicate with the crew on board. The internet connection is relatively slow when compared to what we are used to here on earth, and has very high latency due to the vast distances that the signal has to cover in order to reach its destination. The ISS – at an altitude of 400 kilometres above the earth (also known as low earth orbit) – has to first beam its signal to one of these geosynchronous relay satellites, which can sometimes reach altitudes 90 times higher than that of the ISS. The satellite then beams the signal to a ground station where it processes the request and replies via the same request path.